Historically employment is closely tied to recessions, and that is no accident. One of the primary factors in calculating whether the economy is officially in a recession is an increase in the unemployment rate.

Historically employment is closely tied to recessions, and that is no accident. One of the primary factors in calculating whether the economy is officially in a recession is an increase in the unemployment rate.

But defining the unemployment rate is more complicated than you would expect with different “levels” of unemployment based on how long you have been unemployed and whether you have actually been looking for a job or not. The government has six different classifications of Unemployment from U-1 to U-6.

Skip to Large Chart

See What is U-6 unemployment? for more details.

Historical Employment Levels During Recessions

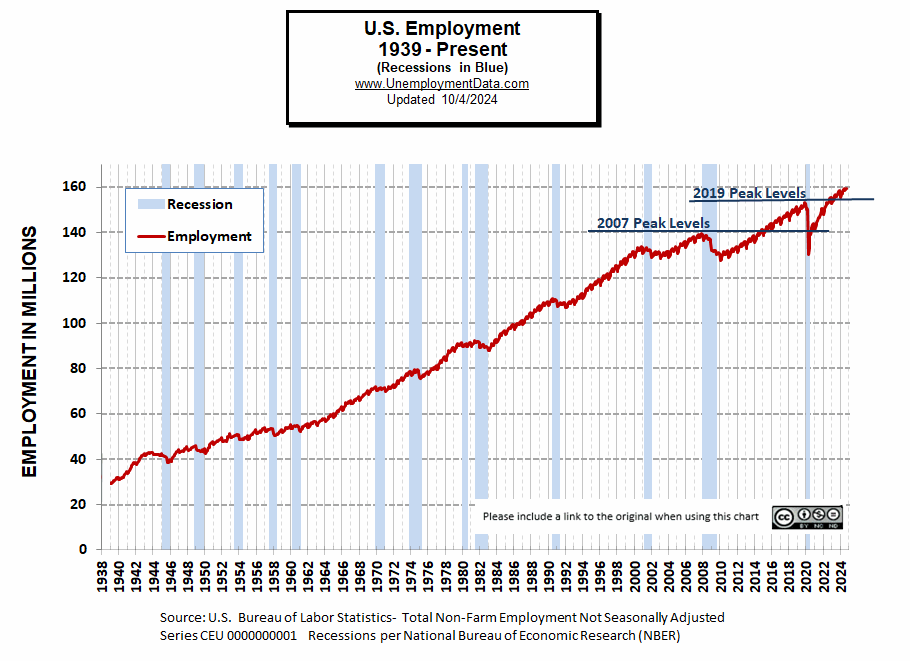

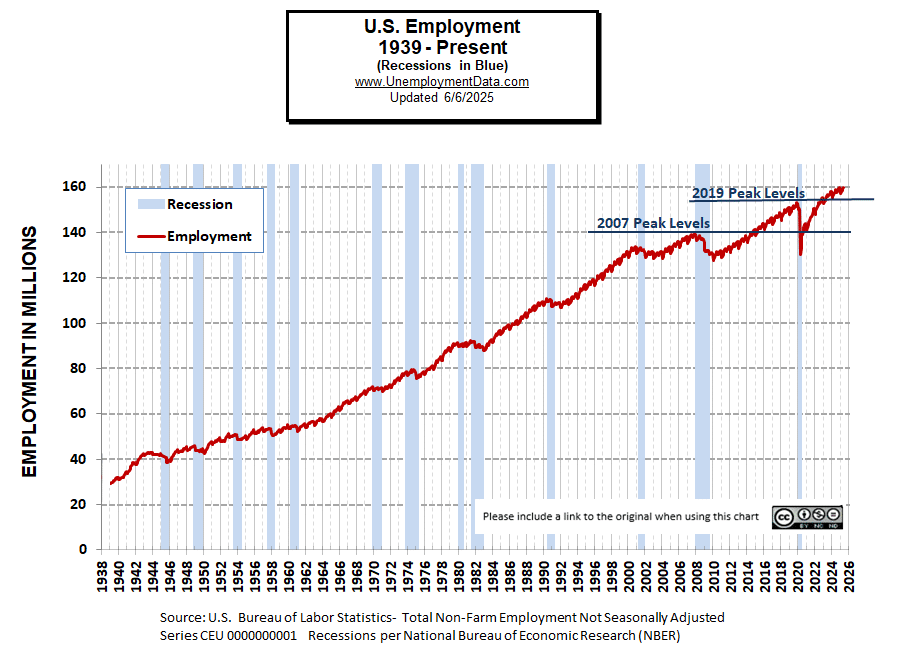

In this chart, we can see the historical employment data from 1939 through the present. But in addition to the number of jobs, we can also see the recessions shaded blue as per the official description of a “recession” by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). As you would expect, recessions correspond pretty well to the declines in employment (i.e., increased unemployment), primarily since NBER uses unemployment as one of the factors to determine whether there is an official recession. However, there are periods classified as official recessions where the number of employed people has not fallen significantly.

The NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP as some organizations do. Instead, they define a recession more nebulously as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales”. Even if GDP or employment don’t decline, but other factors do, NBER can still classify it as a recession. Also, they measure a “cycle” from peak to trough.

When these factors start declining, they say the recession began, and when it starts rising again, they say it ended. Even though times may still be reasonably good when it starts declining and they may still be reasonably bad when it starts rising. Also, if you look at the two periods during the early 1980s with a small break in between, you will see that it was probably a recession during the whole period, and it never really recovered in between.

Defining a Recession According to NBER

The following quote is NBER’s explanation of how they determine a recession:

Factors include “real personal income less transfers (PILT), nonfarm payroll employment, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, employment as measured by the household survey, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions.”

NOTE: As of July 19, 2021, NBER determined that a sharp upturn occurred only two months after the 2020 recession started, so officially, the recession bottomed in April 2020. The previous peak in economic activity occurred in February 2020, making it the shortest recession on record, i.e., from February 2020 through April 2020, but NBER didn’t make its final determination until July 2021. But in spite of the very sharp nature of this “recession,” unemployment was still above 6% a full year later, in April 2021.

NOTE: It took NBER 15 months to declare that the recession had ended. So their determination is certainly NOT “real-time”.

Another thing we can see from the chart is that prior to the 2020 drop, the 2009 employment drop was the steepest decline since 1939 and had one of the longest-duration recessions during that period (unless we consider the entire period from January 1980 until November 1982 as a recession). Supposedly, according to official calculations, there was a brief period between those two recessions… in actuality, there wasn’t much recovery during that period, and employment was basically flat. So perhaps, in an effort not to make the mistake of declaring an end to a recession to soon they are waiting longer to be sure it really ended.

NBER Data Used:

- Total Non-Farm Employees,

- Employment Level,

- Industrial Production,

- Manufacturing Sales,

- Real Personal Income,

- Real Personal Consumption,

- Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP),

- Real Gross Domestic Income (GDI),

- Average GDP vs. GDI.

All the Data NBER looks at on one page.

Note: When they use the term “Real” they mean “Inflation Adjusted”.

Recession Frequency

Another interesting thing to note based on this chart is the frequency of recessions. From 1945 through 1961, recessions occurred approximately every four years. Then there was a ten-year stretch with no recession as technology boomed from 1961 through 1971. Four years later, another recession, then came an unusual sort of double recession from 1980 through 1983. And then, about eight years later, there was another recession in 1991. The next downturn occurred ten years later, in 2001. and in another eight years, there was the “Great Recession” of 2008-2009, although some might argue that it lasted through 2013. So we were certainly overdue for another recession and thus we got an ultra short recession after the extreme recession of 2008-2009.

Historical Employment Data: How Many People Are Employed?

One of NBER’s primary factors in deciding whether the economy is officially in a recession is an increase in the unemployment rate. The chart below provides the Historical Employment Data overlaid on blue bars showing periods of official recessions. We can see that in 2020, the number of employed people fell below the 2007 peak, nearing the lows of the 2008-2010 crash, then rebounded to above the 2007 peak level.

In September 2022, at 153.204 million, employment finally exceeded the 2019 peak of 153.095. But the 2022 population was almost 5 million higher, so how can the unemployment rate be the same? The answer is that a smaller percentage of people are in the workforce, and unemployment only measures the percentage of the workforce that is unemployed.

This also explains why companies were having a hard time finding employees, i.e., the workforce is smaller, so there is a smaller pool of people to choose from. See Employment-Population Ratio for more information. The November 2019 peak occurred at 153.094 million, and in November 2022, employment reached 155.519 million before retreating. In November 2023, employment was 157.953 million. And in November 2024 employment was 159.882.

Source: This chart shows the actual number (unadjusted) of Nonfarm jobs in the United States as tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Historical Employment Data Series CEU 0000000001

As we can see from the table below, from November 2007 to January 2008, there were over 3 million jobs lost, but that wasn’t all that surprising. Typically, January suffers from a reduction in Seasonal workers. Even good years like 2005-2006 saw a decrease of 3 million workers, and January 2008 employment levels were still above January 2007 levels. But by January 2009, year-over-year losses exceeded 4 million. By 2010, the economy had lost another 4.2 million. 2011 showed almost a million jobs improvement, but the economy was still on shaky ground. It wasn’t until January 2014 that the economy reached January 2007 levels, and January 2015 exceeded January 2008 levels.

| Date | Employment in Millions |

| January 2007 | 135.316 |

| November 2007 (Peak) | 139.492 |

| January 2008 | 136.251 |

| January 2009 | 132.022 |

| January 2010 | 127.804 |

| January 2011 | 128.760 |

| January 2012 | 131.095 |

| January 2013 | 133.062 |

| January 2014 | 135.471 |

| January 2015 | 138.491 |

| January 2016 | 141.073 |

| January 2017 | 143.374 |

| January 2018 | 145.413 |

| January 2019 | 147.879 |

| November 2019 (Peak) | 153.094 |

| January 2020 | 150.057 |

| February 2020 | 150.966 |

| March 2020 | 149.952 |

| April 2020 (COVID Crash) | 130.252 |

| May 2020 | 133.421 |

| June 2020 | 138.507 |

| July 2020 | 139.105 |

| August 2020 | 140.728 |

| September 2020 | 141.957 |

| October 2020 | 143.566 |

| November 2020 | 144.117 |

| December 2020 | 143.604 |

| January 2021 | 140.975 |

| January 2022 | 147.932 |

| January 2023 | 152.689 |

| October 2023 | 157.531 |

| November 2023 | 157.950 |

| December 2023 | 157.828 |

| January 2024 | 154.942 |

| February 2024 | 156.007 |

| March 2024 | 156.612 |

| April 2024 | 157.438 |

| May 2024 | 158.256 |

| June 2024 | 158.772 |

| July 2024 | 157.771 |

| August 2024 | 158.070 |

| September 2024 | 158.527 |

| October 2024 | 159.352 |

| November 2024 | 159.882 |

| December 2024 | 159.943 |

| January 2025 | 157.095 |

| February 2025 | 157.944 |

| March 2025 | 158.402 |

| April 2025 | 159.238 |

| May 2025 | 159.964 |

Employment Numbers are “Preliminary” for two months before the BLS considers them finalized due to late-arriving data. Although the BLS does another adjustment in January (sometimes going back decades). If you would like to see pre- and post-revision numbers since 2010, they are here.

You would think tracking Employment data should be much more straightforward than tracking Un-Employment. Working as little as 1 hour a week forces the employer to report that job’s existence to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Every month the Bureau of Labor Statistics surveys about 141,000 businesses and government agencies, representing approximately 486,000 individual worksites, in order to provide data on employment, hours, and earnings of workers on nonfarm payrolls. They tabulate this in their Current Employment Statistics (CES) program. About 40% of the establishments surveyed are businesses with fewer than 20 employees, but this survey generally doesn’t include self-employed individuals. But for some reason, the BLS went back 20 years and changed all the numbers in January of 2013 (only a little at first, but the difference grew more significant as time went on). See BLS Changes Employment Numbers for the details.

Theoretically, the employment data presents a more reliable way of looking at jobs than the unemployment rate, and many countries like England focus more on the “millions employed” than on the unemployment rate. From the above chart of Historical Employment Data, you can see the number of jobs that are filled at any given time and thus the number of employed people.

If the employment numbers are falling, that’s bad and usually correlates with a recession. If the number of jobs increases, that is good and generally means the economy is picking up. The number of jobs bottomed in January 2010 at 127.3 Million, then rose to 131.5 Million in November 2010. Unfortunately, nothing increases in a straight line, so then it lost 3 million and got back down to 128.3 Million in January of 2011. In June of 2011, we topped November’s number by reaching over 132 Million. Again, the number of jobs fell in January 2012 to 130.6 million and then began rising to reach 134.5 million people employed in June of 2012, then rose to 135.6 million in November 2012 and fell to 132.6 million in January and rose back to 134.485 million in March and 137.942 million in November 2013.

One apparent reason for the massive increase in jobs since 1939 is the increase in the population. Another is the exodus from farms to nonfarm labor, as people took jobs as everything from car mechanics and welders to IT professionals. Also, an increasing number of women entered the workplace. These factors put a growing percentage of the Civilian population into the workforce. One recent counterbalancing trend is the decrease in teenage employment. Since 2000 the employment rate for teenagers has fallen from 45% to around 30%.

See Teenage Employment Plunges. Another factor is people retiring early, perhaps due to downsizing and being unable to find another job. However, some people of retirement age have found it necessary to take lower-paying jobs, thus the increase in seniors in retail positions, such as Walmart greeters and cashiers, making it more difficult for teenagers to find jobs.

For more information, See:

- Current Unemployment Rate Chart

- Current Employment Data

- The Misery index measures inflation plus unemployment and is a good measure of the discomfort of the country’s population.

- Current Employment vs. Unemployment Chart is Not just two sides of the same coin.